Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

“Ethical Challenges in Ventilator Allocation During COVID-19 Crisis Level Care in a Low-Resource Setting, Subtitle: Who Gets the Last ventilator?”

*Corresponding author: Lenora Fernandez MD, University of the Philippines Manila, Pulmonary Laboratory, Philippine General Hospital, Taft Ave,Manila, Philippines.

Received: February 17, 2023; Published: March 23, 2023

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.18.002454

Introduction

The need to fairly allocate mechanical ventilator use during crisis care. The COVID-19 pandemic has put an extraordinary strain on public health systems so that medical resources had to be rationed. The most problematic resource to be rationed is the mechanical ventilator because of the limited time for a patient’s life to be saved by ventilator use. The problem is heightened in low-resource countries, such as the Philippines, where there were only 1572 ventilators before the COVID-19 pandemic and, at the projected crisis level, 3,144 more were needed [1]. One of the system responses to such scarce resources needed to save lives is to have a triage system to fairly allocate ventilators. Trigging or fair allocation of scarce critical and life-saving resources by the health care system is a widely accepted public health measure during critical or disaster conditions [2,3]. It is based on the duty of stewardship of the health system and the principle of justice with the ethical utilitarian aim of providing the greatest good to the greatest number of people. Most societies consider it ethically valid for the public good to gain precedence over the traditional non-pandemic priority of providing the fiduciary optimal standard of care to each individual patient [2,4]. Thus, the never-ending moral conflict between how to balance the fair allocation of such an important life-saving equipment, the mechanical ventilator, among the excessive number of patients needing it versus the fiduciary duty of rendering medical care to each individual to save his or her life is faced primarily by the frontline physician and the whole health care system and society as well.

It is, therefore, the intention of this paper to analyze the ethical challenges in mechanical ventilator allocation during a crisis scenario such as the COVID-19 pandemic, in resource-constrained settings such as in low to middle-income countries (LMIC).

?Ventilator Allocation in Crisis Scenario within the Public Health & Systems Context

Ventilator provision for life support is considered as a process

or an intervention within the systems engineering perspective of

public health with input factors to make it happen and specific

outcomes in mind upon implementation of the process. The main

stakeholders who will benefit, or be harmed, from this intervention

are

1) the patient and his/her family

2) health system with the health care givers directly caring

for the patient

3) the public/society

The ethical dilemma of ventilator allocation is complicated because the agents affected by the intervention or active noninstitution of the intervention are different and have differing ethical principles being prioritized so that favoring of one may violate the other principles.

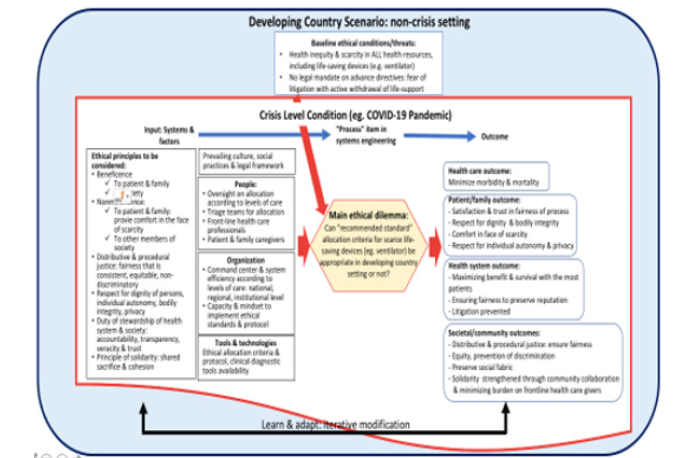

Below is the figure depicting ventilator allocation within this inputprocess- outcome systems framework. The input factors are the people, organization, tools & technologies, ethical principles to be considered and the prevailing socio-cultural and legal framework. The intended outcomes are divided into clinical or health care outcomes, patient & family outcomes, health system outcomes and societal/community outcomes. These are the main stakeholders as well in this issue and if there are differing outcomes intended, then there clearly will be conflict and a complicated ethical dilemma that will ensue.

It is also evident in this schema that several factors affect the process of ventilator allocation beyond ethical considerations and that the scarcity of ventilators is a singular process or event within the bigger picture of pre-existing and long-standing health care resource scarcity or inequity before and, probably, after the crisis state. The schema also emphasizes that the system’s approach is iterative and can easily be modified to adapt to dynamic changes in such a volatile setting such as crisis care (Figure 1) [5].

Figure 1:Overall Schema on the Ethical Dilemma of Allocation of Scarce Resource (Ventilator) in a Crisis-Level Situations in Low-Resource Setting: Input-Process-Outcome Systems Approach [5].

The system’s approach schema, being outcome-oriented, reflects a utilitarian perspective as well. However, it is still not sufficient to give normative guidance in the prioritization of the ethical problems nor the outcomes for the act of ventilator allocation. The different ethical considerations need to be analyzed separately to lend normative guidance to this difficult problem.

Ethical Considerations in Fair Allocation of The Mechanical Ventilator in the COVID-19 Pandemic

Tham commented that “the question on allocation of scarce medical resources continues to be one of the most difficult issues confronting bioethics today” [6]. Many ethical guidelines on scarce resource allocations during crisis level situations have been formulated and the most fundamental principles given recognition are the respect for each human life having its own intrinsic value and that each person has the right to health and to live. It is, thus, the moral duty of each member of the health care system to provide care and preserve life, irregardless of a person’s race, status, gender, ethnicity, age, or physical condition. This also adheres to the principle of beneficence where the health care giver, by giving a life support measure, acts to provide the benefit of preserving the person’s life.

Crisis level situations such as what happened at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic surges, however, placed the health care professionals in a problematic condition because life support measures of ventilator provision could not be given to all the persons in need due to the overwhelming number of critically ill patients compared to the available number of ventilators. The crisis level scenario is an essentially unjust situation where the principles of justice and fairness have to be brought to fore to respect the intrinsic dignity of all persons needing critical care and provide guidance to the stewards of health care so that they will be able to fairly allocate or ration this vital life-saving intervention.

Principles of Justice in Scarce Resource Allocation Decisions/

In making decisions on who should get a scarce vital health

resource and when, the three rationing principles of substantive

justice are often accorded priority and these are the

1) Need principles

2) Maximizing principles

3) Egalitarian principles [7]

Under the need principle, the resource is distributed in proportion to the “need” or “in proportion to the degree of immediate threat to life” [7]. The most immediately ill has the priority and this leads to the “rule of rescue” where the system has the obligation to rescue the persons facing immediate threats to their lives. In this regard, the ventilator becomes a binary resource because its immediate provision will lead to the rescue of a life or not and, thus, makes the rationing decision even more crucial. The binary decision of allocating ventilators becomes even more complicated when choosing a ventilator to be given to a certain person would mean depriving another person of that ventilator and, subsequently, not being able to rescue that other person’s life.

This need principle of justice is most popular among health care givers so that the “rule of rescue” or “prioritizing the worst off” almost always takes priority and clinicians state that “we don’t think there should be discrimination on any grounds other than clinical need” [7,8]. Since there will be different gradations of clinical need, objective scoring measures have been developed to assist the clinicians to reliably quantify and determine this need such as the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score and the Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) [2,3]. Clinicians can more objectively decide who is the most critically ill and who will most have a better outcome when immediate interventions are instituted. However, some parameters in these scoring systems need laboratory results that are not immediately available and, more importantly, are not absolute in reliability since some studies have shown that COVID-19 patients who were assessed to have poor prognoses with these scoring systems actually survived [3].

The second rationing principle of justice of maximizing benefit requires that the resource be distributed to bring the best possible consequences for the whole population [7]. This maximizing principle is most popular among public health experts and has been considered to be almost synonymous to the whole concept of justice in the crisis level scenario. It is utilitarian and consequentialist in focus with the intention of maximizing “aggregate population health” rather than having the individual patient as the primary focus [7]. This utilitarian principle implies that the scarce lifesaving resource (e.g. ventilator) will be allocated to the individual patient who is “expected to gain the largest total amount of health over his remaining lifespan” to the exclusion of this resource to those patients who would gain the least [7]. Judgment is then made on who these individuals will be who would gain the most and the least and is crucially dependent on what these health gains are as set by the society. This, again, entails considering the prognosis of a patient as to who will have the best outcome and not on who is the worst off. Since the COVID-19 pandemic experience has shown that the younger ones and those with fewer co-morbid conditions have better survival rates among the critically ill, then several guidelines have set a higher priority to younger patients and those with less co-morbidities for ventilator access [2].

Such prioritization according to age and presence of comorbidities for the utilitarian purpose of maximizing benefit in ventilator allocation has set off an intense ethical debate and objections on grounds of discrimination [4]. It also contrarily aggravates any pre-existing inequity in life support allocation as those who are older and more frail are the persons who are incapacitated to access hospital-based critical care in the first place [9].

Maximizing benefits has been considered a “paramount” principle in the guidelines of many developed countries on ventilator allocation to the extent that “removing a patient from a ventilator… to provide it to others in need is also justifiable” [2]. Emmanuel further explains that “many guidelines agree that the decision to withdraw a scarce resource to save others is not an act of killing and does not require the patient’s consent” [2]. Some European guidelines on ventilator allocation in the COVID-19 pandemic do not completely agree with Emmanuel’s statement on the withdrawal of ventilator support without requiring patient’s consent to maximize benefit but these guidelines have also not explicitly stated the difference between non-initiation of ventilator support and active withdrawal of ventilator support [4]. By the principle of double effect, it is ethically wrong to perform an active intervention, that is withdrawal of ventilator support from an intubated person, that would lead to his loss of life, so as to lead to the consequence of maximizing benefit for the common good. The active withdrawal of life support would only be ethically valid in cases of medical futility and with the consent of the patient or his surrogate decision-maker.

The third rationing principle of justice is the egalitarian principle where health care is distributed to reduce “inequality” or to equalize the opportunity to access ventilator use as life support [7]. Equality is prioritized among patients with similar prognoses and the recommended strategies are through random allocation by lottery and by the “fair innings” approach [2]. The argument for the “fair innings” is that everyone is entitled to a similarly long and healthy life and, thus, “lifetime health” should be equalized [7]. This argument translates to younger persons being prioritized for ventilator allocation rather than the older persons who have already experienced a large segment of a long and healthy life.

These principles of justice are combined to address the complexity of rationing life-saving scarce resources and the way how these principles are combined and weighted together differ with no specific ethical framework recommendation. Other values and ethical principles are also considered in all guidelines to formulate cohesive, ethically valid and implementable recommendations.

Other Ethical Principles Considered in Ventilator Allocation in the COVID-19 Pandemic

The importance of the role of the health care givers has been undeniable in the COVID-19 pandemic and because of their instrumental value, guidelines have also recommended that priority be given to them as one of the first recipients of ventilators should they fall critically ill. In a system though where there is lack of transparency, the prioritization of critical workers can easily be abused [2].

The right to self-determination, which usually holds the highest importance in non-crisis health care scenarios, has been relegated to secondary position to concerns on justice in rationing scarce resources in crisis care. Nevertheless, “promoting respect for the patient’s autonomy as far as the resources available allow” has resounded in most guidelines [4]. On the ground, informed consent is still required in all interventions performed on a patient, thus, the patient’s right to self-determination has not been forsaken at all [10].

The ethical principle of nonmaleficence in ventilator allocation has bearing in possible ventilator withdrawal and could be violated in situations where the patient is not terminally ill nor considered in a medically futile state.

As the burden of the duty of stewardship is predominantly on the health care system and personnel during crisis times, a paternalistic approach often ensues if left unchecked. The other societal values of solidarity, transparency, veracity, accountability, inclusiveness, openness to communication and change have to be emphasized and institutionalized to ensure that respect for persons and justice be indeed practiced in the procedural and implementation aspect [11].

Unique Ethical Considerations in the Allocation of the Mechanical Ventilator in Low-Resource Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As seen in Figure 1, low-resource settings and low to middle income countries have the perennial problem of health inequities being present even during non-pandemic times [12,13]. Such inequities are heightened when life-saving resources become even more scarce during pandemics. The African authors stated that the burden of deciding who will get the last ventilator has not happened to them yet since most of their population is young and have fallen less ill to COVID-19 compared to the higher resource countries [13,11]. The Philippine author, on the other hand, is in favor of fair allocation strategies proposed by majority of the ethicists in the higher resource countries [12]. It is worthwhile to note though the caution given by the African and Brazilian authors, as well as those who have voiced their misgivings about the allocation process, that the societal factors are very different in the low resource countries so that how the same ethical principles for fairness in allocation will translate in the real-life scenario in ventilator-scarce and ICU-scarce settings could also be entirely different [12,13]. In the Philippines, for example, there is no law allowing advanced directives, hence, the active removal of the mechanical ventilator can be legally called as an act of homicide or murder.

In a recent virtual panel discussion on ventilator allocation in the Philippines, representatives from a patient advocacy organization, frontline critical care physicians, medicolegal, and bioethicist experts expressed their opinions and they had differing recommendations on the cases presented [1]. The foremost consideration of the patient advocates was ensuring that the vulnerable sectors of society are not discriminated. They regarded the egalitarian-based recommendations of allocation by lottery and fair innings as well as the maximal benefit-based suggestion of allocating ventilators to the least frail as highly discriminatory against the frail, elderly and persons with disability who are the ones least taken cared of even during conventional health care settings. The frontline physicians expressed their high level of moral distress because of lack of guidelines and other moral agents who can share their burden of decision-making on allocation. The medicolegal expert emphasized the lack of a legal framework supporting advance directives, hence, expressed caution on measures that may be construed as deprivation of life support. A bioethicist expert oriented the discussion to the moral responsibility of upholding the appropriate ethical principles in allocation decisions, regardless of whether these are made in a low-resource setting or not. Another bioethicist emphasized the need for open communication and engagement with the community in all decisions made on rationing guidelines to foster solidarity and acceptance of such critical decisions on life and death.

Ethical Recommendations for the Fair Allocation of Ventilators in Low-Resource Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As noted in Figure 1, scarcity of life-saving resources, such as the ventilator, in LMIC’s during crisis level care is not a new phenomenon and has existed even before the pandemic and is merely exacerbated by the crisis. The socio-economic and anthropologic determinants of health inequity and poverty in LMIC’s are the same determinants that push the problem of ventilator allocation to a very urgent matter. Since these longstanding socio-economic & anthropologic determinants of health inequity cannot be solved at an instant to help mitigate the ethical dilemma of ventilator allocation and may, most likely, remain well beyond the crisis onslaught, rationing decisions have to be made with these inherent inequities in mind. Other interventions aside from rationing decisions, such as innovative means of increasing ventilator supply and redistributing ventilator availability throughout the country, need to be strengthened as well.

In the low-resource setting where the public is already accustomed to scarcity and inequities, all the more is there a need for formal policies and guidelines to navigate the tricky business of scarce resource allocation [13]. Otherwise, the public will regard paternalistic allocation decisions with mistrust and, coupled with the lack of a legal framework for life support withdrawal, occurrence of such withdrawal of life support as consequences of allocation decisions can easily escalate to malpractice and criminal accusations. Formal protocols and guidelines serve as evidence of upholding the duty to care and of stewardship on the part of the health care system and staff.

The different ethical principles utilized in allocation guidelines in the developed countries should also be used in the LMIC’s. However, the combination and weighting will be different with particular avoidance of measures that can worsen pre-existing inequities. The egalitarian measures of fair innings, random allocation and “first come-first served” basis that are supposed to level off inequalities can heighten pre-existing inequalities when these measures will, most likely, be performed in a non-transparent manner and be abused to favor those proximate to the health care system or staff [3]. While there is a lack of guidelines in any crisis setting, the “first come-first served” basis as a default decision criterion will, however, continue.

The duty to treat the worst off or the duty of rescue will prevail as the first decision point and the succeeding principle of justice that will most be appropriate is that of the proportionate need principle where due emphasis can still be given to the vulnerable populations who might have been relegated to the population with least gain in the conventional maximizing benefit principle of justice. The utilitarian perspective can benefit the LMIC’s by ensuring that one of the targeted outcomes or common good should be the mitigation of the pre-existing inequities in health resources, manpower, information and access.

Even with the best triaging or allocation guidelines, “it is naïve to expect that rationing principles will be consistently followed in practice, and the best we can hope for is to identify better procedures for making decisions” [7]. In a recent survey on adherence to allocation guidelines in an area in the US, it showed that most hospitals created guidelines for the COVID-19 pandemic and their content and application by the frontliners were indeed quite varied [14].

The common recommendation for allocation guidelines in the LMIC’s is the careful procedural aspect of ensuring a “communityengaged approach” that mobilizes “available local resources and expertise” [13]. Only by upholding the principles of solidarity, open engagement, transparency, veracity and accountability can allocation decisions be made less painful and acceptable in the LMIC’s where health inequities are pre-existing and will probably continue to exist even after the COVID-19 crisis. The communities in LMIC’s have been made resilient by chronic exposure to scarce resources but, as many health care systems have managed to innovate to adapt to the challenges of the pandemic, then the LMIC’s can also take this opportunity to innovate and adapt the measures in allocation decisions that lessened inequities during the pandemic to the post-pandemic & conventional health care setting. The setting up of virtual triage committees to assist the frontliners on a real-time basis on allocation decision-making was documented to work in Africa and similar measures can easily be adopted elsewhere [11,15].

Conclusion:

Health crisis-level situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, has brought the challenge of ethical allocation of scarce life-saving resources (e.g. mechanical ventilator) in the face of sudden demand by critically ill patients. The principle of justice by maximizing the benefit of such an important resource for the most in society is acknowledged by most to prevail as the most important principle to guide resource allocation. In low-resource settings, such as low to middle-income countries, with pre-existing health inequities in health care resources and absence of legal framework supporting advance directives, the maximizing benefit principle is tempered with proportionate need focused on the vulnerable population sectors that may have suffered from inequities even before the COVID-19 crisis. The procedural aspect of the allocation decision formulation and implementation should ensure community engagement with solidarity, openness, veracity, transparency and accountability as values to be consistently manifested. Painful decisions will still be made at the frontline on who will receive the life-saving ventilator or not, but, as long as there is transparency and community participation in these decisions, then “the decisionmakers will be able to live with these decisions and not carry it on their conscience” [12].

Acknowledgements

None..

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- TVUP (2021) Webinar #58: Who get the last ventilator? COVID-19 Crisis-Level Hospital Care.

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, et al. (2020) Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382(21): 2049-2055.

- Supady A, Curtis JR, Abrams D, Lorusso R, Bein T, et al. (2021) Allocating scarce intensive care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic: practical challenges to theoretical frameworks. Lancet Respir Med 9(4): 430-434.

- Teles Sarmento J, Lírio Pedrosa C, Carvalho AS (2020) What is common and what is different: recommendations from European scientific societies for triage in the first outbreak of COVID-19. J Med Ethics 48(7): 1-7.

- Ehmann MR, Zink EK, Levin AB, Suarez JI, Belcher H, et al. (2021) Operational Recommendations for Scarce Resource Allocation in a Public Health Crisis. Chest 159(3): 1076-1083.

- Tham JS (2007) The Secularization of Bioethics: A Critical History. Rome, Italy: Ateneo Pontificio Regina Apostolorum. doi: https://www.academia.edu/8008282/The_Secularization_of_Bioethics_A_Critical_History

- Cookson Richard, Dolan Paul (2000) Principles of justice in health care rationing. J Med Ethics 26(5): 323-329.

- World Health Organization (2020) Ethics and COVID-19: resource allocation and priority-setting.

- Biddison E, Gwon HS, Schoch SM, Regenberg AC, Juliano C, et al. (2018) Scarce Resource Allocation During Disasters: A Mixed-Method Community Engagement Study. Chest 153(1): 187-195.

- Buckwalter W, Peterson A (2020) Public attitudes toward allocating scarce resources in the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0240651.

- Naidoo R, Naidoo K (2021) Prioritising 'already-scarce' intensive care unit resources in the midst of COVID-19: a call for regional triage committees in South Africa. BMC Med Ethics 22(1): 28.

- De Castro L, Lopez AA, Hamoy G, Alba KC, Gundayao JC (2020) A fair allocation approach to the ethics of scarce resources in the context of a pandemic: The need to prioritize the worst-off in the Philippines. Dev World Bioeth 21(4): 153-172.

- Moodley K, Rennie S, Behets F, Obasa AE, Yemesi R, et al. (2021) Allocation of scarce resources in Africa during COVID-19: Utility and justice for the bottom of the pyramid?. Dev World Bioeth 21(1): 36-43.

- Ghandi R, Gina MP, William FP, Kelly Michelson (2021) Regional Variation in COVID-19 Scarce Resource Allocation Protocols. medRxiv preprint: 1-24.

- Moodley K, Ravez L, Obasa AE, Mwinga A, Jaoko W, et al. (2020) What Could "Fair Allocation" during the Covid-19 Crisis Possibly Mean in Sub-Saharan Africa?. Hastings Cent Rep, 50(3): 33-35.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.